Phishing scenario metrics for awareness and Red Team assessments

tldr; I have an opinion about the effectiveness of phishing attacks to measure the state of security awareness within an organization. Measurability is great, but there are quite a few ifs and buts. By creating a tool, ethical hackers can make phishing emails more realistic and measurable.

When you think of phishing campaigns or security awareness programs, you might think of the apparent emails that appear in your email box once in a while. These emails were necessary to see whether everyone is still alert on phishing risks and can distinguish a phishing email from a legitimate email. The number of clicks on the link displayed in the emails, how often credentials have been entered, or whether recipients have downloaded and exported a file from the attachment are tracked at a time. Excellent for the report to show that the organization is doing everything to prevent you from being compromised by an attacker through this well-known way of social engineering. These figures are beautifully displayed in a report, including colorful pie charts with an increasingly lower click rate, and the organization has again met the compliance requirements. On to the following assessment!

Because that’s the goal of security awareness testing, right? Increase the awareness of the employees and thereby reduce the click rates? Because the fewer people click on a link in a phishing email and enter data or execute malware, the better the prevention worked out against these types of attacks? Of course: if nobody fills in their credentials on a page or executes that macro from a Word document on their system at all, you will avoid a lot of trouble. But fair; you cannot prevent it entirely. In an earlier post (which is Dutch, but the paper is in English) was stated what the three main reasons are why someone interacts with a phishing email or website1: 1. because the person has insufficient knowledge about what a phishing email is, 2. because the phishing email looks so legitimate that the person cannot distinguish it from an actual legitimate email or 3. because they are not paying attention at the time of receiving the email. And the latter makes it difficult. Maybe you haven’t had your double espresso in the morning yet, you have been in long Teams meetings all day, or you want to quickly clear your email before closing your laptop for the weekend: you are just not there with your head for a while, and you click. And you enter your credentials. Or you download something. That can happen because that’s just human behavior. So using security awareness to completely prevent someone from clicking or filling in credentials or downloading malware is simply impossible. Fortunately, there are other preventive measures for this, such as proper network segmentation, user role separation and a bunch of detection mechanisms, and a good response process.

The attentive reader saw, however, that it can be improved to decrease click rates. And with the click rate, hopefully, also the number of credentials entered and malware executed. Staring blindly at ‘the number of clicks on a phishing link’ may say something about awareness, but less about the risk that the organization runs. With only one click as an attacker, unless it contains an exotic browser attack, you can’t compromise someone. But under the guise of probability calculation and ‘return on investment’ you can leave that out in this context.

Employees don’t have basic knowledge about phishing emails

Multiple security threat landscape reports, such as the Dutch one for 2020, state that organizations are still not sufficiently resistant to phishing but that basic measures can limit the damage. If you want to make phishing less effective, an awareness campaign can ensure that these emails are detected faster and, above all, reported by employees. In practice you often see that during awareness moments (or interventions) certain characteristics about phishing emails are imparted to employees, such as checking out the sender address, inspecting the link (sometimes you even have to pay attention to whether there is a lock in front of it: really!) or the attachment and checking the spelling errors in the email. This indeed ensures that some (simple examples) of phishing emails are detected.

Employees are not able to distinguish a legit looking phishing email from a real legit email

But attackers don’t sit still either. Since a many organizations provide correct information about the dangers of phishing and how to recognize these emails, attackers are busy making emails look as legitimate as possible to pass this trained human detection. Emails don’t contain spelling mistakes anymore, addresses of the sender are very nicely typo squatted, are spoofed, sound legitimate within the context, or are previously used expired domains, contain the correct corporate identity and possibly personal information. This information was obtained from public password breaches or simply from your public social media. In the latter cases, it might involve spear phishing, but a simple web scraper is also set up in such a way to personal information about you. If this attacker uses a credible sender, error-free text with any victim’s data and a copy of the corporate identity, the employee’s basic knowledge will not be sufficient to single out this email as a phishing email. And in that case, you could also look at such an email differently.

Phishing emails that are sent all have one goal: they want something from you. Attackers wish you to click a link and enter your credentials on a legitimate-looking website, download a file from the website, or open the attachment in the email. With the obtained login data, these attackers will try to enter the internal network (via remote desktop or VPN solutions), cloud services such as Office 365, or gain access to your system by using malware. And to get what you want, you use a bit of psychology. Cialdini and Gragg2 have both researched which approaches work best in a phishing email and read as follows:

-

The principle of commitment, reciprocation, and consistency - Within this principle creating and maintaining a good relationship between the victim and the attacker is paramount. When Alice asks Bob to do something for her, Bob will do it (reciprocation) to maintain the correct contact or relationship (commitment). Then Alice will do something in return for Bob in the future because he helped her in the first instance (consistency). In phishing emails or on websites, you see this reflected in the form of coupon codes, for example. You just made a large purchase at webshop X last week, so you will receive a code for a discount on your next order as a good customer. Since your purchase was a good experience last time, that coupon code gives you that final push you needed to order something new. Web store employees indeed are intelligent people.

-

The principle of social proof - This principle is all about peer pressure: if all your friends buy a new iPhone, big chance you also will. But it goes further than just friends, and especially Booking.com is a rock star in doing this; it says on the website that the hotel you are looking at has just been booked by four other people from the same country, so you may also be tempted to book this hotel. Websites use locations from profiles and your location obtained from your IP address, among other things.

-

The principle of liking, similarity, and deception - People quickly trust people they consider themselves to resemble; you soon trust someone who acts the same as you because you think it is the right thing to do. If Alice sends a message to Bob and they have the same background, the same pets, or come from the same region, it creates a bond. If you use this information as an attacker, a victim will believe you more quickly. An example is sending an invitation to a conference: if you see that the sender works in the same sector in the same neighborhood, you will open that attachment in your email faster than if it is less relevant.

-

The principle of authority - From childhood, you are told to obey rules and authority such as the police. Therefore, a victim is more likely to respond to a message that appears to come from a police officer or the CEO of the company. In interventions, emphasize that the authorities and official governmental organizations never send you an email requesting data or payment.

-

The principle of distraction - You soon notice when you have to multitask: you are just a lot better at finishing your work if you can focus on it. However, when you have a lot on your plate that you must complete simultaneously, you are much more susceptible to techniques that attackers use to trick you. For example, if something in an email or website such as ‘Confirm your purchase within a minute to take advantage of this discount’ is stated, you will have to take immediate action. As a result, you will be less critical of the email or website and what you actually want was doing.

This list actually a vital principle: the principle of curiosity. People are curious from nature. If the attacker sends an email to the victim that stimulates that curiosity, the victim can or will fall for it. Examples are an email reminding you that you have not yet paid for a product, a message from a person on a dating site, or the launch of a new intranet.

In addition to telling employees about the essential characteristics of a phishing email, it is also advantageous to say something about using social engineering and how attackers use the mentioned principles to get things done. Consider carefully what feeling is evoked when you open an email. Do they offer you something for free? Is it an email saying you have been fined in an unknown place? Should you act right now? Or are they trying to take advantage of your goodness (helpfulness)? Be careful; ask someone else for help, browse to the organization’s website or webshop (by entering the URL yourself), or if necessary, pick up the phone and contact the so-called sender (but of course not on the number in the email!). Set up two-factor authentication: if you have entered your credentials, it will be useless without a second factor. And, of course, report the email. Do not make it too difficult for your employee: presenting a flow chart of what to do when you have received a phishing email can even be done better by the Dutch Tax Authorities (their slogan: we cannot make it more fun, but we can make it easier). Options are reporting plugins in Outlook or an email address to which specifically phishing emails can be forwarded that is easy to remember.

Reliably test this awareness and make it measurable over a more extended period

Send an email with tips and tricks to all employees, organize a classroom training, show how easy it is to hack someone, or let everyone do e-learning. Or, in short: increase the awareness of employees by intervening. Such an awareness session is good to get everyone on their toes but must be repeated regularly to keep everyone alert. Research from German universities shows that intervention through interactive or video methods is the most effective and should be repeated twice a year3. In order to check whether the form of intervention had an effect, awareness programs are launched where a phishing email is sent by or from the organization once in a while. You can conclude the effectiveness of these interventions over time. What is rarely looked at is what precisely this phishing test measures. Of course, you test the number of clicks, but to what extent does this say something about the employees’ awareness? Often, the exact content of all phishing emails within a program is not determined at the outset. For example, in the first email a scenario where you are asked by a spoofed address to go to an Office 365 login page clone and then download a fact sheet of a page that resembles Sharepoint and in the second email (with some spelling errors), asked by an unknown sender (price@flostracizedent.ru) if you want to download a file to see if you have won a new iPhone, yes of course, the second time will show a decrease in clicks! Show the two reports to your CISO, and you get a pat on the back because you managed to get the click rate down: awareness mission successful4.

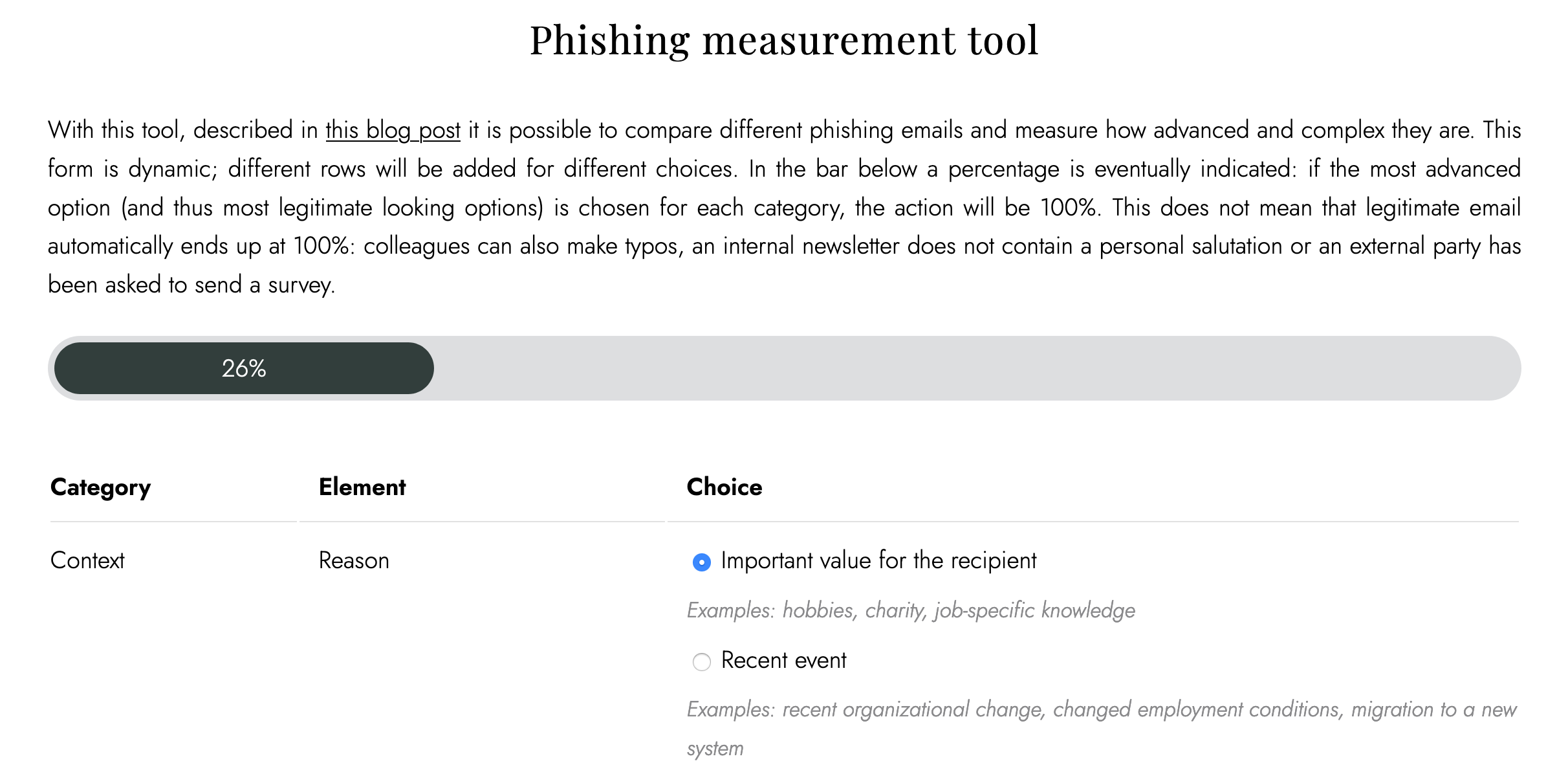

A complex problem has been outlined, but what is a possible solution? By quantifying a phishing email by using a model, emails can be compared with each other. First of all, it is vital to know how a (phishing) email can be recognized. Existing research has already made a model for sites5, but it should be expanded with extra characteristics. Ultimately, an email consists of the context (who, what, where, how is it sent), content (the text, links, images), the domain name, the attachments and the use of security, and confidentiality. Within these characteristics, choices to make are based on Dutch Digital Trust Center and Safe Internet Platform. The result is presented as the model below (click on the image, it is not phishing!):

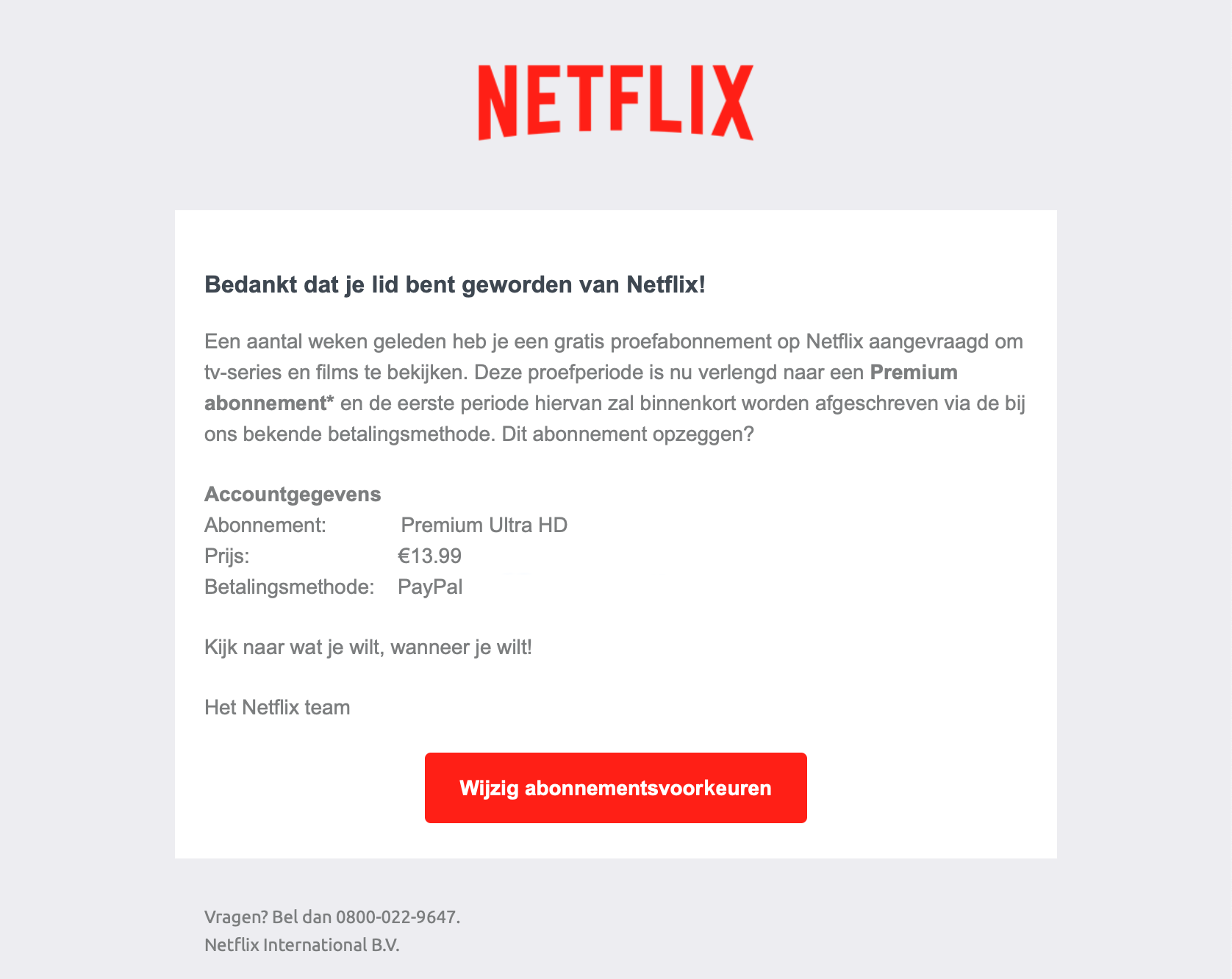

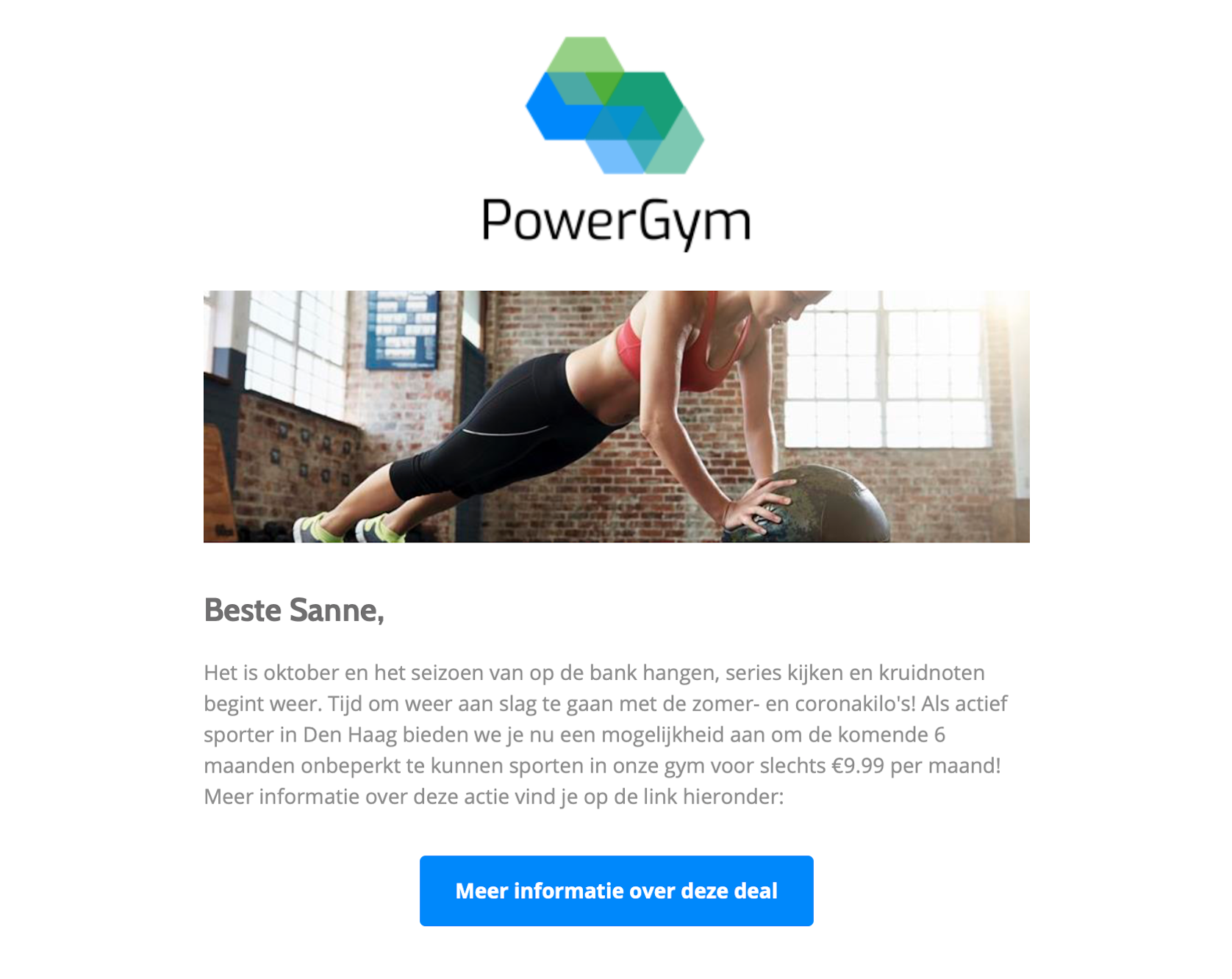

You can subsequently apply this model to existing phishing emails. For example, look at the two examples below and compare them based on content. Both emails don’t contain crazy characters or typos, and are in Dutch (free Dutch lesson!). The Netflix email uses a copied corporate identity (same logo and colors), does not contain any personal information and tries to respond to the recipient’s fear (because money is being debited). The second email (from non-existent company PowerGym in The Hague) uses a neutral corporate identity, responds to recipient’s greed and significant value - who is addressed by the first name. In this way, there is variation within the choices of the content of the email without making it less or more advanced.

Result: the Netflix email scores at 84% and the PowerGym variant at 83% when using the model. The context and content parts have been filled in as shown in the image, and, in addition, Netflix has assumed a typosquat domain, and PowerGym a domain that contains the word PowerGym. Use your wild imagination for the latter because designing phishing emails on your free Saturday evening is a first; creating login pages is going a bit too far :). These 84% and 83% result from weightings based on a single dataset, available literature, and own experience. The weighting may differ per organization, but the availability of more data sets will also lead to more reliable results. For the time being, with a bit of tweaking, the first results look terrific.

Use of the model during Red Team assessments

Phishing tests are not the only way of testing where phishing attacks are being used: Red Team assignments also use this way of social engineering to obtain initial access to the network. Comparing and measuring Red Team assessments is not entirely new. If you run two Red Team assessments over three years, you can compare the techniques used during these two Red Teams. For example, how high is the effort put into initial access / privilege escalation / lateral movement? And has this technique been detected by the Blue Team? Former colleague and brilliant security hero Francisco is one of the ‘founders’ of this project (including more cybersecurity organizations) to make this easier to measure and give organizations a better idea of their prevention, detection, and response. If you zoom in considerably on phishing within the initial access phase, the tool could help indicate how high the effort was in this phase. A small side note: the tool only helps with the scenario itself. The degree to which the malware used is advanced and challenging to detect is not covered by this model. However, it can determine whether it is a low, medium, or high effort technique.

Besides being used after completion of the Red Team assessment, the model can also help with the preparation. For example, in Threat Intelligence Based Ethical Red Teaming (TIBER), an attack by an APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) or other more prominent threat actor is simulated to see how well the organization can defend itself against it. Suppose a specific group emerges from the Threat Intelligence report that is active in organization’s sector being tested. In that case, the emails sent from this actor can be compared with the emails sent within TIBER. Keeping this in mind, you have more certainty that the phishing email sent during this Red Team corresponds in terms of complexity with that of the threat actor.

Take, for example, TA505, known for the attack on Maastricht University in the Netherlands. When you grab two emails from this threat actor sent to Maastricht University (obtained from this forensic report) and a COVID-19-mail reported by Trend Micro. At first glance, there are many similarities: the email is impersonal, addresses a recent event or current theme, and contains a link to a page where a download is offered (a URL where a Microsoft-related service occurs). Both emails, therefore, come to a percentage of 68% (TA505 amateurs!!!). During a Red Team assessment, you could consequently set the difficulty of the phishing email to this but preferably do this slightly higher. An APT has months (or perhaps years) to attack an organization, which you often don’t have during a Red Team assessment (unfortunately). This allows them to vary with emails until this is successful.

But wait, there’s more than clicks

Some platforms offer insight into more than just clicks, but often only this measurement is used to conclude over a more extended period. Lower numbers would mean that awareness has increased. But there is more than just clicks or logins. The same number of clicks with two different (equivalent) phishing scenarios can mean that the awareness has remained the same, but what if a doubling has been seen in the second scenario in the number of reports submitted to the service desk? Employees may have clicked to inspect the page, then reported it, and then clicked away. That is not unsafe behavior (as described earlier). Also, include this in the measurement of how effective the intervention was. Consider the number of employees who show insecure behavior every time, how many employees have correctly completed the e-learning about phishing, or how much is posted on the intranet as a warning for fellow employees. Research organization SANS has defined a metrics matrix6 that helps measure these points and process them in the awareness roadmap. Think about what you will measure, who is responsible for this, the goal, and the target group. Target groups are groups within the organization to which a particular intervention applies. These are defined to create more focused awareness. After all, an organization’s recruiter or financial employee will have to deal more with emails with attachments (because: CVs or invoices) than someone with little customer contact. So consider for each metric to which target group it applies. Educating the entire organization on the basics of phishing, plus additional training on Word macros, PDF files, and other file extensions in the attachment for specific groups, could be a good approach.

Are you inspired to make everything measurable? The SANS institute has defined a Security Awareness Maturity Model in which phase 5 shows possibilities for an excellent measurable security awareness program. This can provide organizations tools for making phishing campaigns and their effectiveness measurable and other components such as safe use of passwords, safe internet browsing, and safe device management. Just make everything measurable, to infinity and beyond!

-

Principles of Persuasion in Social Engineering and Their Use in Phishing ↩

-

An investigation of phishing awareness and education over time: When and how to best remind users ↩

-

Small nuance: of course programs have different learning objectives. You can also look at the awareness level by offering phishing emails that vary widely in level. This way you can also draw a conclusion to a certain extent. ↩

-

Decisive Heuristics to Differentiate Legitimate from Phishing Sites ↩